If this reads like a break-up letter, that’s because it is. Rachel won’t receive it, and that’s fine. Her pool of fans is large enough, so she won’t notice me quietly slipping out the back door.

If this reads like a break-up letter, that’s because it is. Rachel won’t receive it, and that’s fine. Her pool of fans is large enough, so she won’t notice me quietly slipping out the back door.

My first experience with Rachel Held Evans was with her first book, Evolving in Monkey Town, and it was a breath of fresh air. It was 2012 and we were coming off a year-long break from church. We’d discovered we weren’t Baptist anymore, so when we moved back to Tennessee we hesitated every Sunday morning. That hesitation turned into an altogether protest. Exhausted of politics from the conservative pulpit and no answers to hard questions (or even an attempt to answer them), I needed a long hard break.

Rachel’s story was similar to my own. I felt like she had snatched ideas from my brain, a comforting realization that I was not alone.

Her second book, A Year of Biblical Womanhood, was another watershed experience in 2013. She took Proverbs 31 and turned it upside down, or maybe she turned it right side up. Either way, she stirred my theological brain in a new way – pushed, pulled, swirled. I walked away feeling like a lot of it was meant for me. I tossed the bits that I thought were unnecessary, but mostly, Rachel was speaking to me about God in a new way.

Fast forward to 2014, then 2015, and mostly 2016. Rachel’s Twitter feed became less and less about God and the church and more and more about Hillary Clinton, the Democratic Party, and snide, shoddy remarks about the other side. Sometime last summer, I unfollowed her. I don’t care what she believes politically. I care what she wrestles with theologically. That’s what drew me to her in the first place. The empathy I once saw in her was gone. She had left the conservative church, but by all accounts, she didn’t hate them.

That’s not the case anymore.

I knew from the very first sentence that I was going to struggle with the book. Glennon Melton of Momastery wrote the Foreword, and the first line produced one of the biggest eye rolls of my life:

I mean, seriously. The world would still turn.

Side note: Something fishy is going on in the writing world and I don’t like it. Writers are being collected and folded into a super-duper high-profile club – like Oprah pulling Rob Bell into her prominent ring of spiritual experts alongside Glennon and Liz Gilbert. Rachel’s book was fraught with club references – Nadia Bolz-Weber, Sara Miles (people I read in 2014, 2015) … Watch out, Jen Hatmaker. You’re next.

I understand there is a larger, underlying marketing equation at work here. If you read one writer, you’re likely to read one who’s similar. It makes sense from an economical, book-selling point of view.

But for me, it cuts credibility. This club of writers all reference each other, all say the same thing, all boost one another’s books on their websites and social media. They’re on TV together and in conferences together, and now they are all on my nerves. It’s annoying. I wish they’d stop.

Actually, it’s fine. They can continue. Their fraternizing just pushes me back to C.S. Lewis and Thomas Merton.

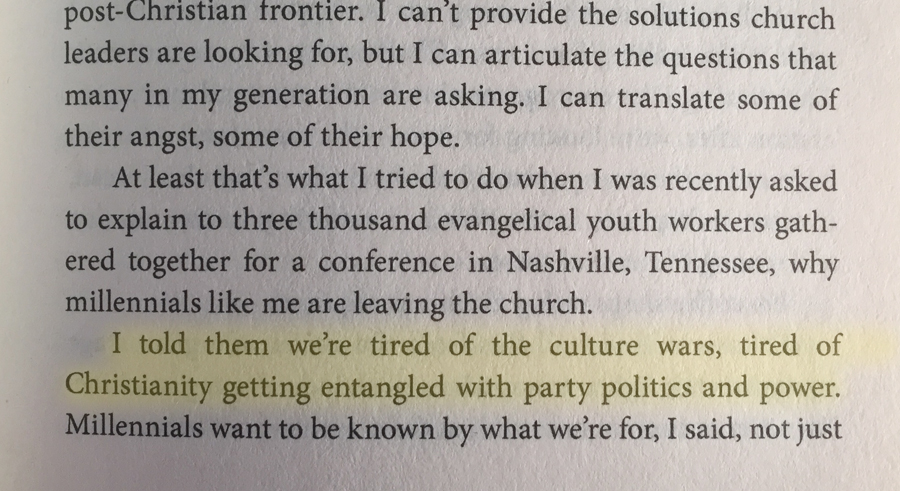

Once I got over myself (and the Foreword), I got into the actual book and settled in for a dose of Theological Rachel. I wanted to know how her searching for a church had gone in the last few years. I had hopes that the book would not mirror her Twitter feed, and when I read this line, I thought, yes, she understands. We are tired of party politics in church!

But then…

There was one jab…

… after another jab…

… after another jab.

Let me summarize: God made everyone and loves everyone, and everyone should have a place at the communion table, but thank goodness we saw the light and are not conservative Republicans anymore. WHEW!

There is good stuff to be found in this book, such as her chapter on Communion (the book is broken into sections by sacraments – totally something I’m into). She quotes Nora Gallagher, saying, “On those days when I have thought of giving up on church entirely, I have tried to figure out what I’d do without Communion.” This remark spoke right to me, as it’s been a big reason I’ve continued to attend church when I’ve really wanted to ditch it.

The chapter on oil under Anointing the Sick was also moving and gave me much to think about in the way of marrying eastern and western medicine with eastern and western theology in regards to healing.

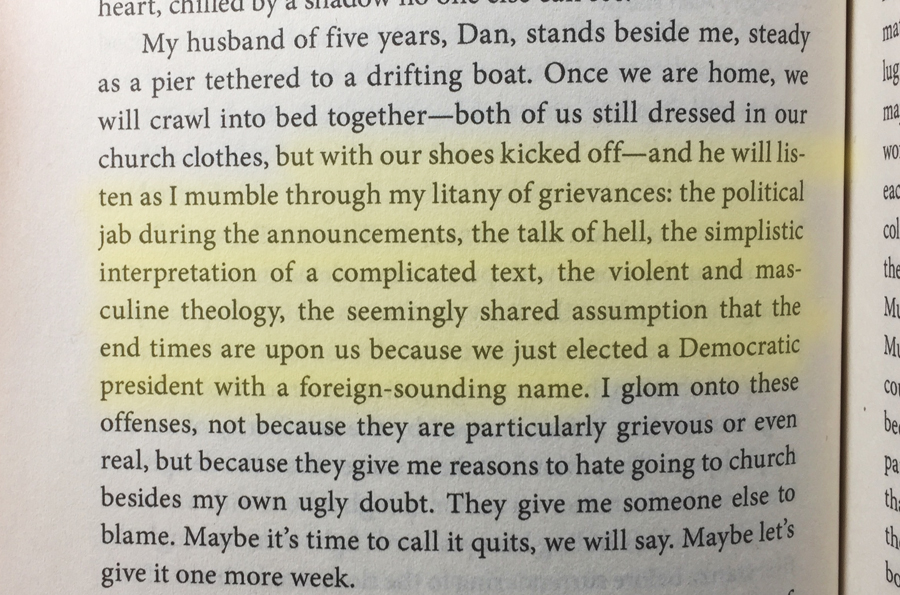

But those flashes of inspirational thought are greatly overshadowed by Rachel’s political pin pricks. They may accurately reflect her personal marriage of religion and politics, but she overshot on assuming all of her readers would relate. She misunderstands that progressive theology does not always parallel progressive politics.

More so, the intermittent political comments beg the question: Are you shaping your politics through a theological lens, or has your theology changed to suit your politics?

Again, her credibility is cut.

I’m not a Republican, so her pin pricks were not necessarily directed at me. But I’m also not a Democrat, so I don’t understand the camaraderie she’s boasting among her fellow liberal Christian writers.

Ultimately, the fact that I’m even referencing political parties in a book about God and the church tells me that I’m no longer Rachel’s audience.

For what it’s worth, the relationship was off to a great start.