When you think of Europe during World War II, the reign of Hitler and his persecution of the Jewish people come to mind. Much has been made of the Holocaust, and rightfully so.

When you think of Europe during World War II, the reign of Hitler and his persecution of the Jewish people come to mind. Much has been made of the Holocaust, and rightfully so.

But only history buffs and folks who retain more than average information from history class will remember that the people living in the Baltic States suffered greatly under Joseph Stalin and Soviet rule. Between 1941 and 1952, more than 130,000 people were deported by force and sent to labor camps across northern Russia and around the Arctic Circle as part of Stalin’s effort to weaken the resistance and cleanse Lithuania, Estonia, and Latvia of those who opposed him. They traveled like cattle in train cars where disease, infestation, and starvation took hold. Families lived in exile, separated from one another, some surviving, many dying, awaiting rescue from anyone who cared.

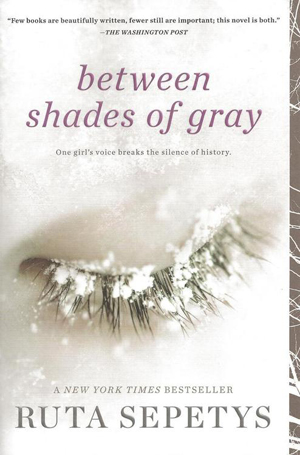

Between Shades of Gray is a fictional account of a mother and her two children, teenage Lina and her younger brother, Jonas, starting on the night they were taken from their home by Soviet law enforcement (NKVD). The novels begins with a chilling scene: “They took me in my nightgown.” The story is told from Lina’s point of view, an artistic girl who survived and documented the experience through sketching.

Author Ruta Sepetys dug deep into her Lithuanian heritage to bring light to a part of history many people didn’t know existed. I certainly didn’t. Amid an already difficult event, there are a handful of scenes and themes that leave me troubled, but I am sure Sepetys only scratched the surface of what the deportations and labor camps were really like.

Because I prefer all-encompassing, engrossing historical fiction from writers like Ken Follett, I found Between Shades of Gray to be lacking in greater detail regarding the political and historical climate of 1940s Europe. However, when I realized this novel was presented initially as a YA book, it made sense to focus on Lina’s experience rather than lay out the multi-faceted map that was World War II. That is the difference between Follett’s thousand-page trilogies and Sepetys’ quick 300-page read.

Even without the padding of historical detail, Between Shades of Gray is an account worth reading, if only to gain perspective on a group of people largely excluded from the retelling of who suffered and died under mid-century communist rule. This is book deserves a permanent spot on high school reading lists everywhere.