I gotta say – I miss fiction. It feels like I’ve been immersed in monks and heretics and religious history for ages, and my brain is weary. There is a stack of fiction books waiting for my attention, but before I even get to those, Chuck’s insisted I read One Second After, which he says will turn me into a full-time apocalypse prepper. (Summer hobby?)

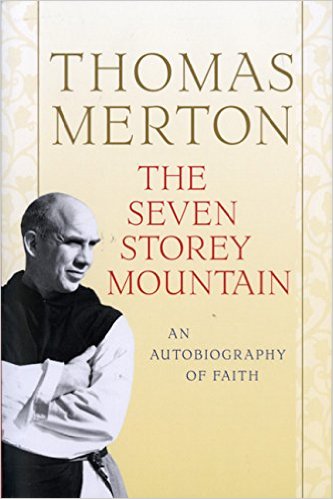

Last night I finished Thomas Merton’s The Seven Storey Mountain. He’s a lengthy writer and seems to leave no word unsaid. However, inside those long paragraphs and chapters is an intimate and critical look into his early life and eventual conversion from no belief system to making a lifelong vow to the Catholic church as a Trappist monk.

Last night I finished Thomas Merton’s The Seven Storey Mountain. He’s a lengthy writer and seems to leave no word unsaid. However, inside those long paragraphs and chapters is an intimate and critical look into his early life and eventual conversion from no belief system to making a lifelong vow to the Catholic church as a Trappist monk.

The book was published in 1948, just a few years after Merton took his vows at the Abbey of Gethsemani in Kentucky (where I’ll be going for a weekend retreat in July). The time frame is important because much of Merton’s life was lived in pre-war France and New York, so there was a constant, ever-present threat of the war that we all know eventually played out. Merton was called up in the draft but was turned away for medical reasons.

More than a dozen pages of this book are dog-eared because Merton wrote something that I need to re-read and consider. Such as:

- We refuse to hear the million different voices through which God speaks to us, and every refusal hardens us more and more against His grace — and yet He continues to speak to us: and we say He is without mercy! (page 143)

- I think one cause of my profound satisfaction with what I now read was that God has been vindicated in my own mind. There is in every intellect a natural exigency for a true concept of God: we are born with the thirst to know and to see Him, and therefore it cannot be otherwise. (page 191)

- All our salvation begins on the level of common and natural and ordinary things. (That is why the whole economy of the Sacraments, for instance, rests in its material element, upon plain and ordinary things like bread and wine and water and salt and oil.) And so it was with me. Books and ideas and poems and stories, pictures and music, buildings, cities, places, philosophies were to be the materials on which grace would work. (page 195)

Though his conversion story is interesting on its own, my favorite part of the story is when he finally submitted himself to the contemplative, quiet life of a Trappist monk. He spends several pages describing the peace and solitude of the abbey, how the silence enfolded him, how the liturgy brought him to tears, to his knees. I am entirely fascinated by the idea that someone would walk away from life – unload all possessions, ideas, and expectations – and commit to a life of service, labor, study, and prayer. Merton suggests that it is the prayers of these few faithful who help keep God’s grace and mercy upon us:

“The eloquence of this liturgy was even more tremendous: and what it said was one, simple, cogent, tremendous truth: this church, the court of the Queen of Heaven, is the real capital of the country in which we are living. This is the center of all the vitality that is in America. This is the cause and reason why the nation is holding together. These men, hidden in the anonymity of their choir and their white cowls, are doing for their land what no army, no congress, no president could ever do as such: they are winning for the grace and the protection and the friendship of God.” (page 356)

1 Comment

Comments are closed.