A couple of days ago I was on a six-mile run while listening to West Cork, an Audible True Crime series, which is set up like a podcast. (If you enjoyed Serial and S-Town, I recommend you give it a try.) The particular episode I was listening to centered around the Irish Garda’s (police) questioning of a murder suspect, and suddenly I was struck by the memory that I, too, had been questioned by the police.

Not for murder, mind you. For fraud, forgery, and theft.

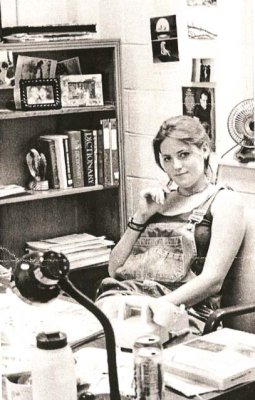

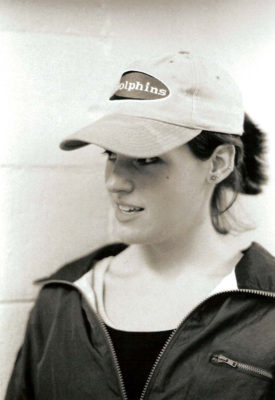

This was me in college. I was an A/B student – only one C, thank you very much, and it was in Geology, a mind-numbing class about rocks.

This was me in college. I was an A/B student – only one C, thank you very much, and it was in Geology, a mind-numbing class about rocks.

This photo was taken in 1998 in my office when I served as editor of the university newspaper. Behind my head on the wall is a poster of Jon Bon Jovi. To my right, on the shelf, is a framed photo of Chuck and me. I was the student who got up early to exercise, rode my bike to campus, hung out in the newsroom when I had free time, and studied hard for every exam. In addition to the newspaper, I also worked part-time at the front desk of a local hotel, an ideal job for a college student because I could study when not helping guests. I had nary a blemish on my record.

Imagine my disbelief, then, when I was called in to the Murfreesboro Police Department for questioning. I had no clue why I’d been contacted, so I started recounting my steps for weeks and months on end. Had I gone somewhere? Had I seen something? Had I done something? Why do police officers look so scary in interview rooms?

I sat down at the table and the two male officers looked back at me. I remember clearly a distinct silence before a file was opened and one of the officers took a breath to speak.

“Do you know why we wanted to talk to you?”

I either shook my head or said no.

The officer read my address to me and asked if I lived in that particular apartment. I said I did. (As a reward for earning the editor position, I moved off campus into my own one-bedroom apartment. The rent was $390 per month and my cat, Precious, was able to live with me.) He asked how long I’d lived in that apartment, and at the time, it had been less than a year.

Then he placed in front of me a series of checks written out to various stores in the local mall. They weren’t checks from my bank account, and my name wasn’t on any of them. He asked if I recognized the checks, and I said no.

He asked, “Are you sure?”

I examined them more closely. They belonged to a woman, evident by the printed name in the top left-hand corner, and they’d been filled out by a woman, evident by the big, loopy cursive handwriting. Still, they weren’t mine, nor were they filled out by me. I either shook my head or said no.

I examined them more closely. They belonged to a woman, evident by the printed name in the top left-hand corner, and they’d been filled out by a woman, evident by the big, loopy cursive handwriting. Still, they weren’t mine, nor were they filled out by me. I either shook my head or said no.

The officer explained that a box of checks had been delivered to my apartment – or rather, the metal mailbox associated with my apartment located at the front of the complex.

“I don’t use that mailbox,” I said. Relief washed over me. “The lock doesn’t work so the door just hangs open. I only use my campus mailbox.”

Another bout of silence.

“Only junk mail gets delivered to the apartment. I don’t use that mailbox. I don’t even check it.”

My relief faded. I realized that whether or not I used the mailbox for my own mail didn’t matter. If a box of blank checks had been delivered there, in theory, I still could’ve taken them and used them.

“I didn’t take the checks. I didn’t do this.”

The checks were collected and set aside, and a blank notepad and pen were placed in front of me. I was to sign my name several times, then sign the name of the person whose name had been forged.

A handwriting sample.

This was the real deal. I was a suspect in a crime. (Cue Law & Order gavel.)

I panicked as I started to sign my own name because I was certain they’d doubt me. As a 20-year-old creative person, my signature was known to change shape. It depended on my mood, my effort, the time I had to sign something. Sometimes it was coiled and messy, other times it was neat and professional.

I endeavored to sign my name authentically. Then, I moved on to the stranger’s name. I signed it over and over again, each on a new line, then I pushed the notepad back across the table so the police officer could inspect it.

Then he said something I will never forget.

“I have to say – this looks very similar.”

He brought the checks back to the center of the table and placed the notepad next to them. Yes, they looked similar, in that twirling, spiraling way every girl’s handwriting looks similar at 20 years old. My heart pounded.

“I didn’t take those checks. It wasn’t me.”

While I have no idea what I looked like sitting at that table, I’m confident I looked a mess. I’ve never been able to hide my emotions. What you see is what you get. Surely, they could’ve interpreted my fear as guilt. The truth was that I wanted to cry and call my parents.

Then, I looked at the dates on the checks and thought of my work schedule at the hotel. Suddenly, it occurred to me that my time could be accounted for.

“You can look at my time cards,” I offered, “at the hotel. I’m sure I was working on those days.”

I went on to recount my work schedule, knowing my time cards would validate that I was seated at the front desk on the clock when the real thief was clothes shopping with someone else’s money. I gave them my boss’ name and number and told them to verify that what I was saying was true.

They let me go with the warning that if my time couldn’t be accounted for I would be contacted again.

Thankfully, my boss provided the life-saving time cards that coincided with the dates written on the stolen checks. I was both grateful my name had been cleared and mortified that it had been associated with a crime in the first place.

I never heard from the police again.

The last thing I did was call the leasing office at the apartment complex to tell them what hell I’d just been through and to get the dang lock fixed on my mailbox.

A year and a half later, when I moved out of the apartment, the lock was still broken and the mailbox continued to be stuffed with junk mail address to “Current Resident.”